A third of your math work is useless

AI predicts confidently how students will do.

At Kwyk, we use AI to predict student’s performance, especially in maths. Our most recent results show that on one-third of the exercises given by the teacher we know beforehand that the student will succeed, raising the question of its usefulness. Despite the clickbait title (sorry for that), the answer might not be as simple as you would expect. We are going to attempt to explain that the biggest threat in AI is not AI in itself, but our human over-interpretation of its results.

Introduction

In this article, we will analyze prediction data done on 1 million maths exercises done between March 7th, 2018 and March, 23rd 2018 on Kwyk. The predictions were done in real time. The training was done on a 5 Million exercises dataset from September and October 2016 results.

Kwyk is an online learning platform where students do their homework online. The students are age 11 to 18 and are assigned homework by teachers on the platform. Each individual has a different homework generated automatically, but all questions are equivalent in terms of difficulty : 1/3 + 1/2 is roughly the same as 2/3 + 1/4 for instance. Because homework is generated, students can retry anytime on a new version of the homework to get the best grade. They can also work freely on any given chapter at any times. To be fair, 90% of the activity is work assigned by teachers.

We also grade automatically every exercise, using formal analysis. This is how we evaluate if a student succeeded an exercise or not. What we evaluate is the probability of success of a student on a specific exercise.

How we got our results

The results were obtained using an AdaBoost regression, on manually crafted features, which included various averages, including the student’s average on this particular chapter for instance. We also used automatically crafted features, which are sort of the map of maths, which we explain in detail here. In total there are 10 manual features and 50 automatic features.

Results summary

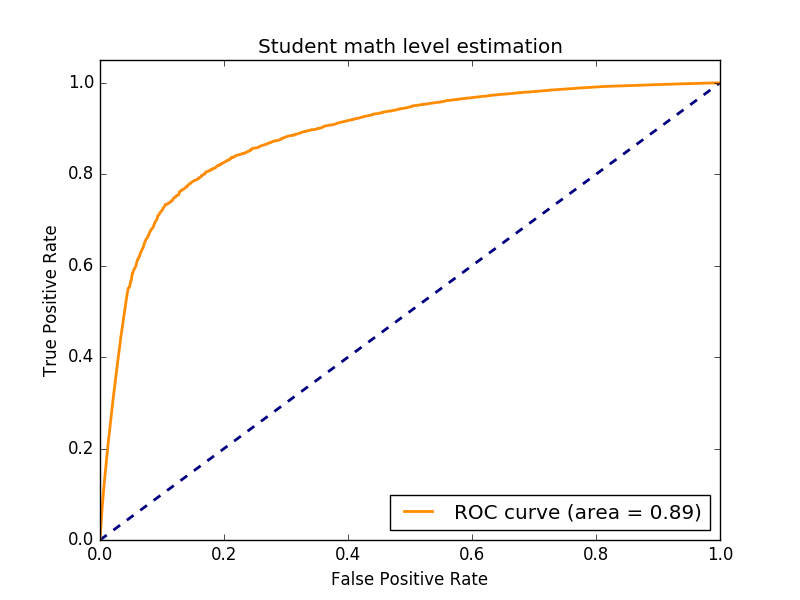

Now the results. First, we get an AUC score of 0.89. Unfortunately, we don’t have an expert reference (different teachers estimating success likelihood of students). Not having comparison points makes it really hard to evaluate if this score is interesting or not. We can only compare to previous versions of our algorithms, which started with AUC 0.72 so we definitely improved our assessment of students, you can read our other articles for details on our algorithms and how we assess them.

Area Under Curve of our predictions (Prediction data was evaluated in real time)

Area Under Curve of our predictions (Prediction data was evaluated in real time)

Out of the 1 Million exercises we assessed, we estimated on 300k exercises that the student would succeed over 95% of the times. They succeeded on average over 96% of the time. In other words, our algorithm was able to predict that you knew how to do this exercise a third of the time. If this is so, was it really necessary for you to do it ? The temptation to answer no is exactly the problem that AI poses to us, humans.

On the other end of the spectrum, we estimated on 100k exercises that the student would succeed less than 5% of the times. In reality, they succeeded 10% of the times. So our algorithm is less accurate on low probabilities. This is expected as we don’t control what happens between exercises, so if a student asks for help or reviews his notes before answering, we have no way of capturing that in our data.

But in the end, it means that we roughly know a student’s result in advance on 40% of the questions asked by his teacher.

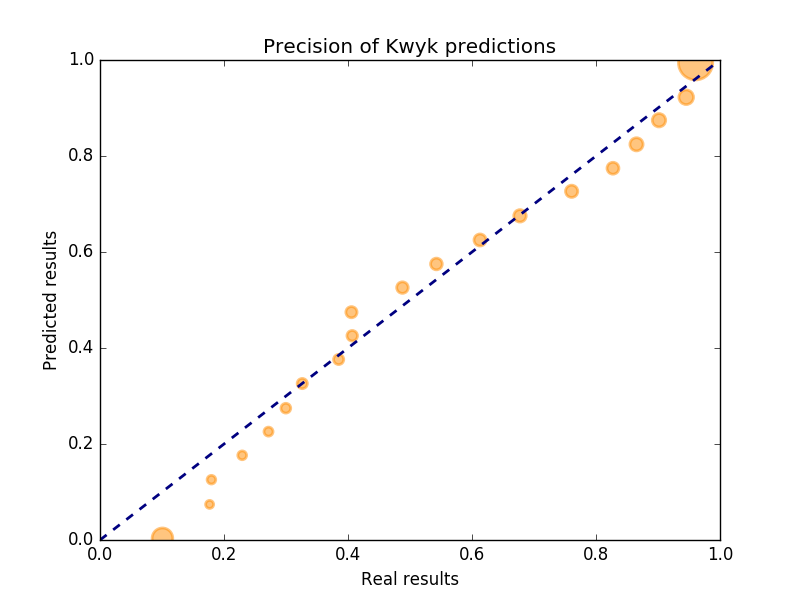

Overall you can see how precise is our algorithm on the following graph

Each dot is a group of predictions. The closer the dots are to the blue line, the better the prediction was for that group. The two big dots at each end are the one mentioned in this article.

With AI we know a student’s result in advance on 40% of the questions asked by his teacher.

Discussion

So 40% of the time we know in advance with a small margin of error if a student is going to succeed at a specific exercise. Why is it that we should NOT conclude that it was a waste of time. There are two types of reasons for this.

The first type of reasons is over-interpretation of the results. The algorithm used tried to assess the likelihood of success of a given student. It was NOT to assess if it was necessary for this student to answer this question (which by the way is a much more difficult question to ask an algorithm). AI works by using correlations. So imagine a new student being transferred to an excellent class that never makes any mistake. An algorithm will most likely categorize this student as being very likely to succeed. This new student will be categorized as “no need to work” even if he did not do any exercise yet. This is obviously wrong.

The error is not in the algorithm, as most students that get transferred into excellent classes will be excellent students, the error is in us humans, that over-interpret what the algorithm says. The likelihood of success is not the proven mastery of a given subject, yet we humans will tend to think that both are the same because we estimate the likelihood of success with our estimate of a student’s mastery. AI does not work that way. Not understanding this is really the core of the problem with AI. Because we cannot ask our algorithms questions like humans, we need to find proxy questions that we hope will be close to our real questions. In our case the real question we would like to ask is “What does this student know”, and the proxy we found is “How likely is he to succeed at this task”.

AI forces us to change our real world vague questions into extremely specific proxy questions. The human confusion between the two questions is the biggest threat to integrating AI into our products.

The same problem is found over and over. Facebook question should be “How to maximize our users’ happiness”, and the proxy they use is “How to maximize view time on our site”. Google’s question is “What is the answer to this user’s query” and its proxy is “What is the link with the lowest bounce rate on this user’s query ?”. Understanding that there is a fundamental gap between the question we would like to ask our algorithm and the actual proxy we use is extremely important if we want to avoid errors in the future.

The second type is related to neuroscience and is specific to this problem. Suppose now that our proxy is perfectly valid to estimate a student’s mastery. Our prediction still does not take into account our human brains. We forget all the time. In order to memorize something, we need to recall it many times. Spaced repetition is an example of how to take this into account. So even if you already know something, if you want to fix it in your memory you need to do it over and over at regular intervals. Once again, even if our algorithm knows that you know something in advance, it might be in your best interest to do the exercise anyway to fix the knowledge in your brain.

In addition to memory, the student’s emotional state is another variable that we might want to take into account when we look at the bigger picture of education.

How to prevent this over-interpretation

Exactly like the Simpson’s paradox, there is no silver bullet here. The main way to prevent over-interpreting is to be extremely conscious of the problem. We, as practitioners, need to be aware of the questions we asked our algorithm and to be extremely careful not to over-interpret the answers they give us. We also need to alert everyone else to the types of conclusions that should not be drawn from our results.

We can also multiply the different questions to ask our algorithms. If many specific algorithms seem to converge on their answers, maybe it is a hint that it could be a good answer to our human questions.

If only we could add dropout to our interpretations…

Further work

At Kwyk we have many goals in order to improve overall student’s success. In addition to ever improving our student’s success estimate, we need to try and address the problems evoked in this article.

For instance, we are looking to take into account the sequencing of personalized sequences (the second type of problems). For this we still cannot ask the human questions, we need to find a proxy question. The proxy question will be “What is the best strategy of homework to give a specific student to maximize his future likelihood of success on all exercises ?”. For this, we will use RL approaches. Of course, we will necessarily encounter problems along the road but we hope we can come closer and closer to answering our real question which is “How do we maximize each student’s success ?”.