A non-NLP application of Word2Vec

Applying Word2Vec to math exam questions.

When using Machine Learning to solve a problem, having the right data is crucial. Unfortunately, raw data is often “unclean” and unstructured. Natural Language Processing (NLP) practitioners are familiar with this issue as all of their data is textual. And because most of Machine Learning algorithms can’t accept raw strings as inputs, word embedding methods are used to transform the data before feeding it to a learning algorithm. But this is not the only scenario where textual data arises, it can also take the form of categorical features in standard non-NLP tasks. In fact, many of us struggle with the processing of these kinds of features, so are word embedding of any use in this case ?

This article aims to show how we were able to use Word2Vec (2013, Mikolov et al.), a word embedding technique, to convert a categorical feature with a high number of modalities into a smaller set of easier-to-use numerical features. These features were not only easier to use but also successfully learned relationships between the several modalities similar to how classic word embeddings do with language.

Word2Vec

You shall know a word by the company it keeps (Firth, J. R. 1957:11)

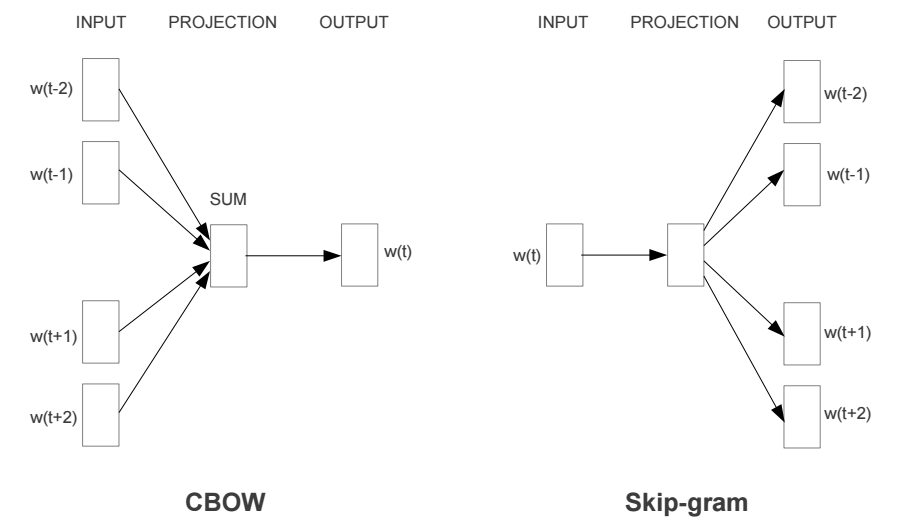

The above is exactly what Word2Vec seeks to do : it tries to determine the meaning of a word by analyzing its neighboring words (also called context). The algorithm exists in two flavors CBOW and Skip-Gram. Given a set of sentences (also called corpus) the model loops on the words of each sentence and either tries to use the current word of to predict its neighbors (its context), in which case the method is called “Skip-Gram”, or it uses each of these contexts to predict the current word, in which case the method is called “Continuous Bag Of Words” (CBOW). The limit on the number of words in each context is determined by a parameter called “window size”.

Both Word2Vec architectures. The current word is w(t) and w(t-2)..w(t+2) are context words. (Mikolov et al. 2013)

So if we choose for example the Skip-Gram method, Word2Vec then consists of using a shallow neural network, i.e. a neural network of only one hidden layer, to learn the word embedding. The network first initializes randomly its weights then iteratively adapt these during training to minimize the error it makes when using words to predict their contexts. After a hopefully successful training, the word embedding for each word is obtained by multiplying the network’s weight matrix by the word’s one-hot vector.

Note : Besides allowing for a numerical representation of textual data, the resulting embedding also learn interesting relationships between words and can be used to answer questions such as : king is to queen as father is to …?

For more details on Word2Vec you can have a look at this Stanford lecture or this tutorial by Tensorflow.

Application

At Kwyk we provide math exercises online. Teachers assign homework to their students and each time an exercise is done some data is stored. Then, we use the collected data to evaluate the students’ level and give them tailored review exercises to help them progress. For each exercise that is answered we store a list of identifiers that help us tell : what is the answered exercise ?, who is the student ? , what is the chapter ?… In addition to that, we store a score value that is either (0) or (1) depending on the student success. To evaluate the students’ levels we then simply have to predict this score value and get success probabilities from our classifier.

As you can see, a lot of our features are categorical. Usually, when the number of modalities is small enough, one can simply transform a categorical feature with (n) modalities into (n-1) dummy variables then use that for training. But when the number of modalities is in the many thousands — as it is the case for some of our features — relying on dummy variables becomes inefficient and impracticable.

In order to address this issue our idea is to use Word2Vec to transform categorical features into a relatively small number of usable continuous features using a little trick. To illustrate, let’s consider “exercise_id”, a categorical feature telling us which exercise was answered. In order to be able to use Word2Vec we have to provide a corpus, a set of sentences to feed to the algorithm. But the raw feature — a list of ids — isn’t a corpus per se : the order is completely random and closer ids don’t carry any information about their neighbors. Our trick consists of considering each homework given by a teacher as a “sentence”, a coherent list exercise ids. As a result, ids are naturally gathered by levels, chapters… and Word2Vec can start learning exercise embedding directly on that.

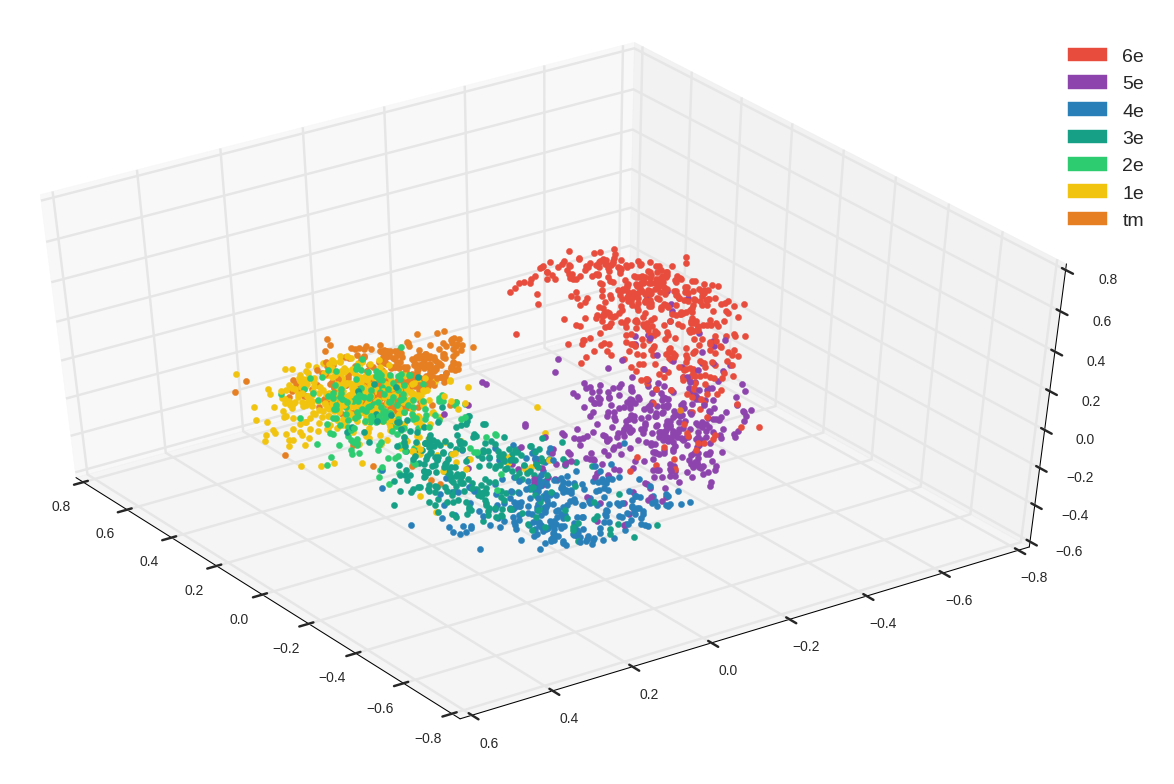

Indeed, thanks to these artificial sentences we were able to use Word2Vec and get beautiful results :

Exercise embedding (3 main components of PCA) colored by level. 6e, 5e, 4e, 3e, 2e, 1e and tm are the french equivalents of the 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th grades in the US.

As we can see, the resulting embedding has a structure. In fact, the 3d-projected cloud of exercises is spiral-shaped with exercises of higher levels following directly those of previous levels. This means that the embedding successfully learned to distinguish exercises of different school levels and regrouped similar exercises together. But that’s not all, using a non-linear dimensionality reduction technique we were able to reduce the whole embedding into a single real valued variable with the same characteristics. In other terms, we obtained an exercise complexity feature that is minimum for 6th grade exercises and grows as the exercises get more and more complex until it is maximum for 12th grade exercises.

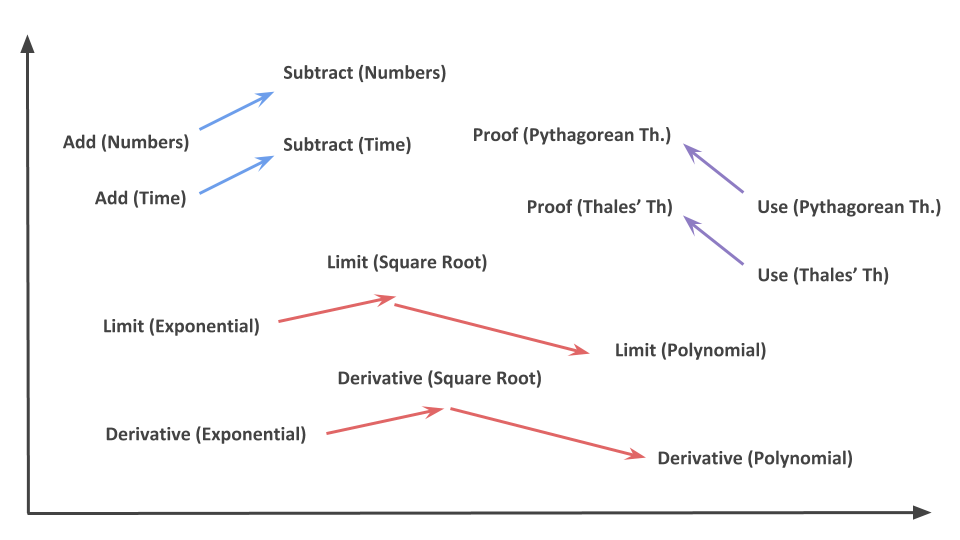

Moreover, the embedding also learned relationships between exercises just like Mikolov’s did with English words :

The diagram above shows some examples of the relationships our embedding was able to learn. So if we were to ask the question “an exercise of number addition is to an exercise of number subtraction as an exercise of time addition is to … ?” the embedding gives us the answer “an exercise of time subtraction”. Concretely, this means that if we take the difference embedding[Substract(Numbers)] - embedding[Add(Numbers)] and add it to the embedding of an exercise where students are asked to add time values (hours, minutes …) then the closest embedding is one of an exercise that consists of subtracting time values.

Conclusion

All in all, word embedding techniques are useful to transform textual data into real valued vectors which can then be plugged easily into a machine learning algorithm. Despite being principally used for NLP applications such as machine translation, we showed that these techniques also have their place for categorical feature processing by giving the example of a particular feature we use at Kwyk. But in order to be able to apply a technique such as Word2Vec, one has to build a corpus — i.e. a set of sentences where labels are arranged so that a context is implicitly created. In our example, we used homework given on the website to create “sentences” of exercises and learn an exercise embedding. As a result we were able to get new numeric features that successfully learned the relationships between exercises and are then more useful than the bunch of labels they originated from.

Credits go to Christophe Gabard, one of our developers at Kwyk, for having the idea of applying Word2Vec to process categorical features.